I’ve had the privilege of chatting with several remarkable scientists, including Nobel Prize winners, but I think it’s safe to say that none of them have been quite like Dexter Holland. As the lead vocalist, guitarist, and primary songwriter for punk rock powerhouse The Offspring, a licensed pilot with a 10-day solo flight around the world under his belt, the creator of Gringo Bandito hot sauce, and a Ph.D. molecular biologist, Holland has quite an incredible resume.

The BenchSci team was thrilled to have Holland join us and share his unique thoughts and perspectives on science, its intersection with art, and what it was like returning to Ph.D. studies after touring the world as a rockstar for 20 years. Here are some of the highlights, including the story of how one of The Offspring’s hit songs was actually inspired by Erlenmeyer Flasks!

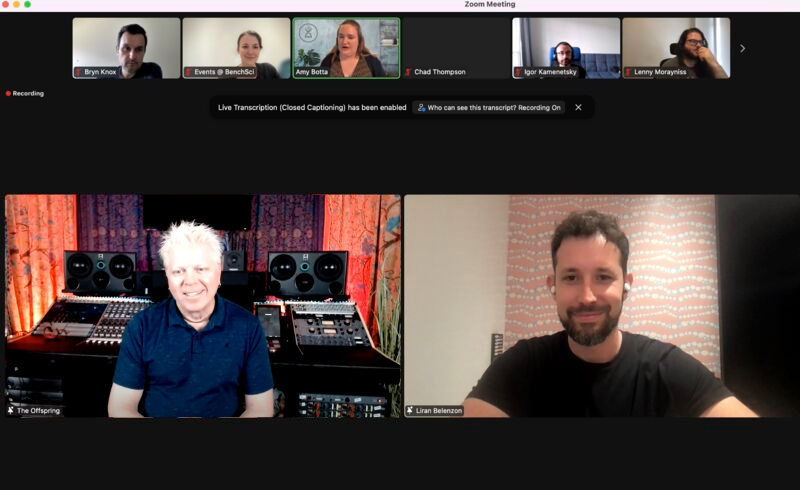

Dexter Holland speaking with the BenchSci team

LB: We’re all familiar with your musical accomplishments, but maybe less so with your scientific career. Could you tell us a bit more about your journey as a science student and what drove you to pursue biology?

DH: I've always been into the math and science side of things. I thought I wanted to be a doctor when I was younger, so I attended the University of Southern California (USC) as a pre-med biology major. As I went through those studies, one of the courses that I found really interesting was molecular biology, especially when we got to the study of viruses. The idea that this strange organism could just take over your cells and use them to replicate itself was something about virology that I found so fascinating.

Though, what I found even more fascinating was the idea that, through medical research, we had discovered ways to assuage these infections and even defeat some of these viruses. I thought it was just so amazing that we could figure out ways to stop these organisms in their tracks.

Unfortunately—or maybe fortunately—I didn’t get into medical school. I don't know; I think everything turned out for the best. But I maintained a great relationship with USC, and later on, they suggested I return and continue as a graduate student. So, that’s what I did for several years, studying molecular biology—virology in particular—because that’s what I had come to love.

Dexter Holland delivering a commencement speech at USC’s Keck School of Medicine

LB: That's a great segue to my next question—what pulled you back to biology? When your third record really took off, you had the choice to be a rock star or a scientist. Obviously, you chose rock star, but then you came back to science. What made you want to come back?

DH: When I started my punk rock band with friends from my old neighborhood, I don't think any of us really had any idea or expectation that it would ever become anything. I mean, the idea of “making it” with the band seemed like a pipe dream—like winning the lottery. But it was something that we enjoyed, and I didn't want to give it up.

I was able to maintain a good balance as a grad student, working in the lab during the week and playing with the band on weekends. That’s pretty much how things went for a long time as I worked on my dissertation for my Ph.D.

Then all of a sudden, the band took off and I had to make a decision. I couldn't juggle both anymore, and I felt like I had this really amazing opportunity with the band that probably wouldn't come again. So I took a leave of absence from USC.

They were very gracious about it. I don't think I actually ever got “kicked out,” so to speak—my leave of absence never expired. And I had great fun for 20 years, touring and making records and all that. But finishing the degree was always in the back of my mind. I felt like it was something I had started, and I wanted to finish it. Eventually, I started meeting with some of the USC professors—some of the people I had worked with previously were still there, but I knew that that window would close eventually. So, I decided it was time to return, and they were nice enough to welcome me back.

They made it much easier than it might have been. I didn't have to take a lot of remedial work—they let me basically pick up where I left off, so that couldn't have been better. I studied part-time, so it took five years to finish the degree, but I finally got it done.

LB: Do you regret anything about your return to science, or would you make the exact same decision again?

DH: I don't regret it. I'm really glad that I finished the degree. I'm glad that I’ve come back to science because I have a place here. I want it to be part of my life. It's just like anything else—finding that balance of the right things in the right amounts.

LB: I know you have a really good story about how science impacted your art, and I was wondering if you wouldn't mind sharing it.

DH: I was actually talking about this in a speech, which I called “The Intersection of Art and Science,” because I think people often consider them to be very separate entities—polar opposites even—and I don't necessarily agree with that.

For example, one time, I was in the lab, and my job that day was to make Petri dishes. Everyone knows what a petri dish is—you have to make them anytime you want to grow bacteria or viruses. You take the plastic part, and you pour this agar gel into it. So, I was preparing gallons of agar gel.

There are these two-gallon Erlenmeyer flasks. You pour water into them, which you then cook to sterilize. Then you have to let it cool down. So, I put these giant Erlenmeyer flasks on the bench, and they weren't cooling down because the liquid inside was so viscous. I thought to myself, “I put them over under the hood where there's ventilation, but they’re still not cooling down.” Then I thought to myself, “these flasks are never going to cool down; you gotta keep them separated.” And it sounds like a silly story, but as soon as I said the words to myself, it sounded like a catchy hook in a song. So, I just started playing with that line and kind of kept going with it.

But I knew I couldn't write a song about Erlenmeyer flasks, so I had to think about something else—what else should you keep separated? And I thought about how my commute to LA took me through some pretty bad neighborhoods every day. I saw a lot of signs of gang violence, and I thought that would be an interesting topic to write about—there’s this societal plague of gangs; what can we do to stop it? But it was really inspired by my work in the lab.

LB: I wonder if you have a similar experience from the other side. After all these years of being a rockstar and now being back in the lab, does your work as a musician ever impact your work as a scientist?

DH: Well, I think of it like, whether it’s music or science, it’s all about solving puzzles. Trying to figure out what’s going on with microRNA in HIV isn’t all that different from taking a catchy line like “you gotta keep them separated” and trying to figure out how the rest of the chorus goes. Sure there are differences—science is generally more methodical, for one—but they’re both still puzzles of a sort. I think the two kinds of activities definitely complement each other.

LB: I was wondering if we could shift the conversation more to the day in the life of a scientist. Could you share with us what, from your perspective, are some of the biggest problems that you as a scientist or scientists as a whole face?

DH: If I'm gonna be in scientist mode, I generally will drive up to USC and spend the day or the week in the lab. My research has gravitated toward data—I don't do a lot of actual wet lab research. If I am going to be involved in something like that, I’ll collaborate with someone else who will cover the wet lab part.

But, you know, data is everything. We live in data, and yet we drown in data. Really the challenge is finding the right data. A simple search isn't always the most helpful. What happens is you get 10,000-plus results, and the only way to find the information you actually need is to dig through them all manually. Sometimes I might come across a paper that identifies another paper that might be number six in a chain of papers. It would be nice if there were a way to trace the lineage of those papers. Anything that can help facilitate getting through the hordes of data is extremely useful.

LB: That's actually very much aligned with everything that we're doing here at BenchSci; developing AI technology to decode all the evidence regarding medical research that’s ever been generated and putting that data at the fingertips of scientists, empowering them to derive the maximum value. That’s really the big challenge we're solving.

What excites you more, being on stage or a big scientific discovery?

DH: I mean, they each have their own unique appeal, but yeah, I'd be lying if I didn't say this: the stage is a pretty fun place to be, for sure. The stage is like a party.

LB: You spent a number of years away from the lab, and then you came back. What do you find has changed the most, and what did you think would change but hasn’t?

DH: The speed is what has changed the most in the last several years. I mean, the first time they sequenced E.coli, it took them years to do. Now you can do all that in less than a day. I think the speed at which you're able to do things is incredible. That's a really great advantage. Of course, the internet brings so many sources of information together, which is great as well.

I struggle a bit to think of something that hasn’t changed. There’s still the bureaucratic element to deal with, I suppose. As I’m sure you understand, the most important thing is empowering individual scientists to do their best work. But bureaucracy does sometimes interfere, whether you're at an academic institution or a company. So I guess that’s something that hasn’t changed all that much, unfortunately.

LB: You obviously have a lot of success in your career. The BenchSci team was wondering if you could share a bit about how you overcome obstacles and deal with failures.

DH: Yeah, failure is always going to be part of life. But, as cliché as it sounds, you can learn a lot from failure. It's very rare for someone to be successful at something initially. I always say that if you want to be good at something, you have to be willing to suck at it for a long time.

The other thing is, the answer is only no until it's yes. You’re gonna have doors shut in your face, but it doesn't mean it's forever. Persistence is just so important—you have to be able to stick with it until you get somewhere.

LB: Do you think music is a science? What parallels do you see between the two, between music and science?

DH: I haven't studied this myself, but I've often heard that people who excel at math are often musically inclined as well. There’s definitely something to it, thinking about it. As a musician, you’re always counting time. I can sort of visualize chord progressions in an almost geometric way—four chords fitting together and following an established pattern. So maybe there is a sort of science behind it, and maybe I do see music in a mathematical way.

Going back to the intersection of art and science, I think there's an element of creativity in science that people don't acknowledge enough—designing an experiment requires creativity. You're trying to think of the best way to solve a problem. You know the question you’re trying to answer, but determining how to find that answer can take quite a bit of creativity.

LB: Now for a hard question: what’s your favorite lab tool, and why?

DH: Well, I'm not that well versed in all the wet work stuff, but I always thought that PCR was just an amazing tool—you can take whatever you're looking for and magnify it a gazillion times in a matter of hours. And it was basically discovered by accident. This is a ubiquitous tool—it's used in everything now—all because someone pretty much stumbled into the discovery that the polymerase from Thermus aquaticus doesn’t get degraded when you cycle it, which is what makes PCR work.

We’d love to hear your thoughts on Dexter Holland’s amazing journey or the intersection between music and art. Let us know in the comments below!

Subscribe to our blog to stay on top of all the latest BenchSci news and events.